The Today Art Museum in Beijing recently hosted “Brilliant and Epic,” an Alphonse Mucha exhibition showcasing nearly 200 original works, from posters and paintings to drawings and decorative designs. Intertwining the splendor of Mucha’s commercial art with the grandeur of his nationalistic narratives, the show intended to reveal the duality of his legacy: a master of Art Nouveau’s aesthetic revolution and a spiritual chronicler of Slavic heritage. Inspired by this exhibition, I offer not a formal review but a personal reflection on Mucha’s art, his destiny as an artist, and the enduring resonance of his vision.

A Personal Encounter: Mucha’s Painterly Mastery

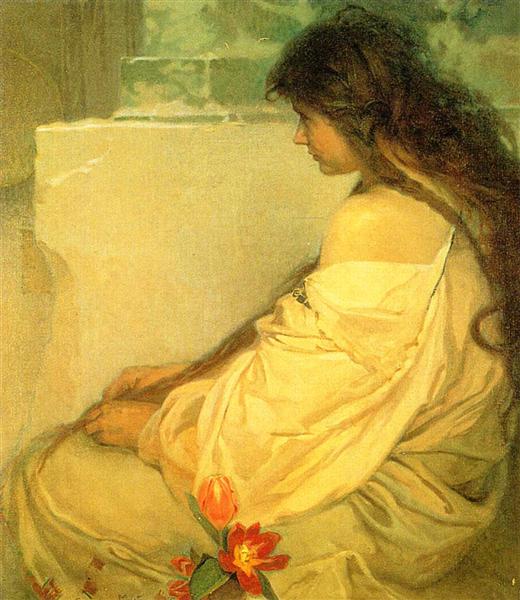

My first encounter with Alphonse Mucha was not through his iconic posters but in a composition class, where I studied two of his 1920s oil paintings: Fate (1920) and Girl with Loose Hair and Tulips (1920). These works captivated me with their bold compositions and nuanced value choices. In Girl, the natural curvature of the seated figure contrasts with the geometric wall behind her, while her cascading hair divides the canvas into expansive shapes. The intricate folds of her dress and the unruly texture of her hair play against the wall’s emptiness, with muted tones punctuated by the vibrant red of a tulip. The result is a serene yet vibrant harmony, a balance of peace and subtle tension. Similarly, Fate juxtaposes a vast cream-white space above with the intricate patterns and folds below, the woman’s intense gaze and powerful hands set against the soft texture of the fabric. Every inch of these paintings feels deliberate, a testament to Mucha’s skill.

My composition teacher remarked that Mucha’s fame as a decorative artist often overshadows his prowess as a painter. I was struck by Mucha’s use of liubai (leaving blank space), a technique central to traditional Chinese painting, where open spaces balance intricate details to achieve a minimalist-maximalist harmony, while guiding the viewer’s eyes without overwhelming them. Walking through the exhibition, it was obvious that the posters and designs reinforced how this harmony, rooted in liubai 留白, distinguishes Mucha’s work across mediums. Furthermore, both his painterly and decorative works were grounded in realistic sketches and live models, revealing a traditional approach beneath his stylized designs.

My composition teacher remarked that Mucha’s fame as a decorative artist often overshadows his prowess as a painter. I was struck by Mucha’s use of liubai (leaving blank space), a technique central to traditional Chinese painting, where open spaces balance intricate details to achieve a minimalist-maximalist harmony, while guiding the viewer’s eyes without overwhelming them. Walking through the exhibition, it was obvious that the posters and designs reinforced how this harmony, rooted in liubai 留白, distinguishes Mucha’s work across mediums. Furthermore, both his painterly and decorative works were grounded in realistic sketches and live models, revealing a traditional approach beneath his stylized designs.

There’s also a personal layer in my appreciation of Mucha’s art. My own maternal grandparents were both decorative artists active in China during the 1930s and 40s. Though I never met them, seeing their surviving works instilled in me an early fascination with design and pattern. One of my grandmother’s paintings (“Peony, King of Flowers”), features twelve female figures representing the flowers of each month, with peonies at the center, echoing Mucha’s fusion of women and blossoms into a harmonious union of humanity and nature. (See more about my grandma’s art and life at Xuying Art Gallery)

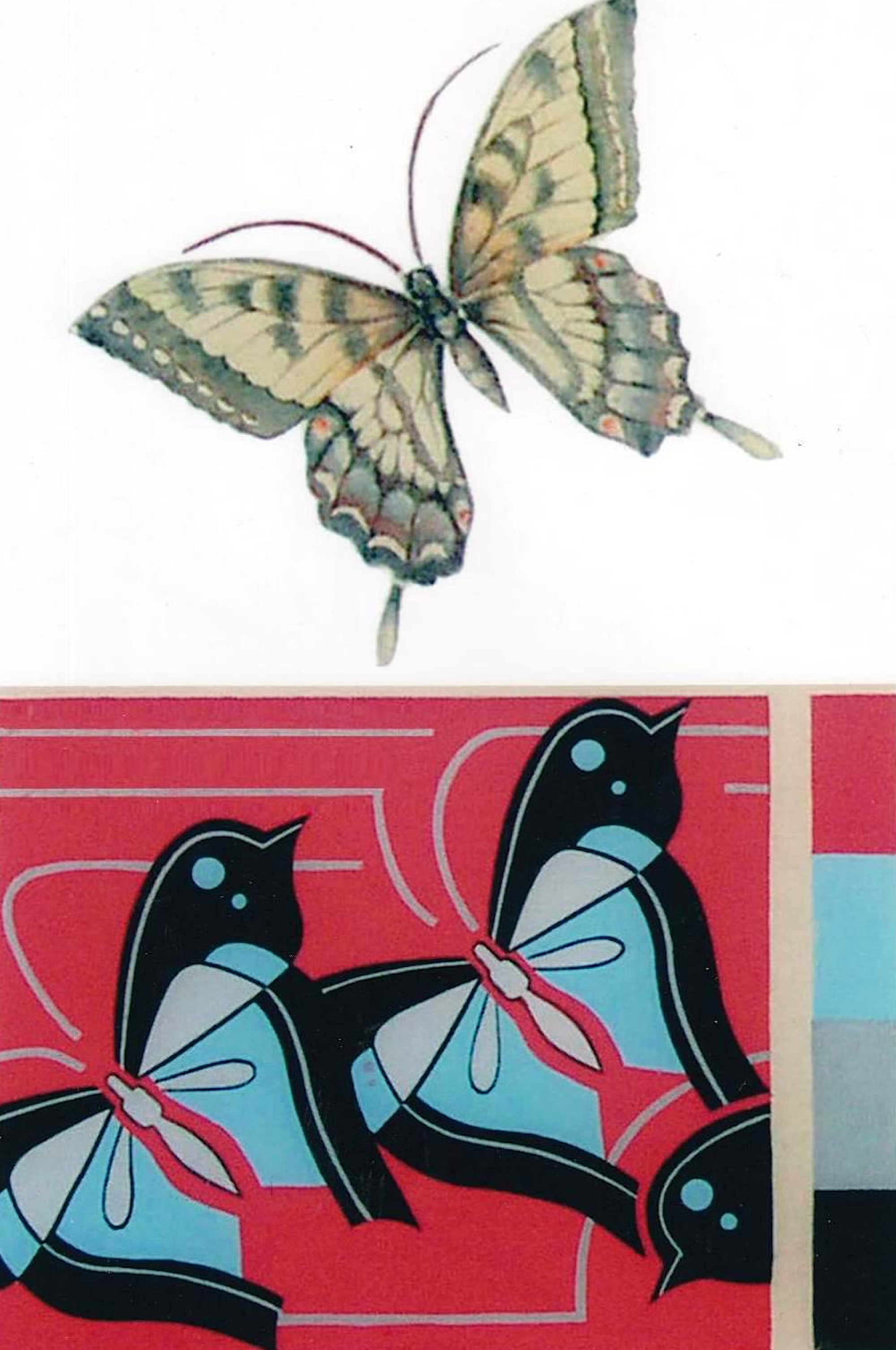

The Beijing exhibition also included Mucha’s Documents Décoratifs (1902) and Figures Décoratives, which illuminate his design process. Starting with naturalistic drawings, he stylized the forms into patterns, further abstracted the pattens to space-filling shapes, and finally applied it to various objects. My grandmother’s sketches, found in her archived drafts, follow a similar path.

The overlapping principles and methods Mucha and my grandparents used in creating artworks make me think that the divide between fine art, decorative art, and even commercial art is so arbitrary – barriers the entire Art Nouveau movement sought to break. Whether painting or designing, for a product or for a gallery, there’s no shortcut to achieving an effective artwork. As long as the artist stays true to his craft and vision, there’s no high or low in the process.

Mucha’s Destiny: Art for the People

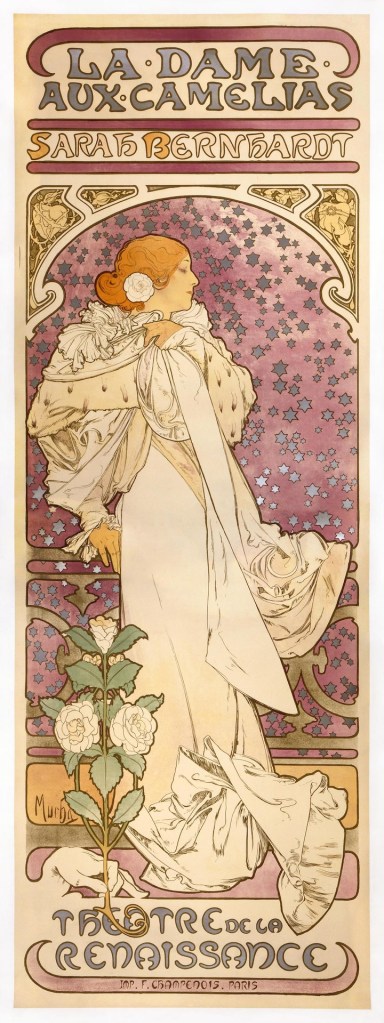

Born in 1860 in Ivančice, Moravia, Alphonse Mucha rose from modest beginnings to become the king of Art Nouveau, yet his ambitions reached beyond artistic movements. Trained in Munich and Paris, his career soared with the 1894 Gismonda poster for Sarah Bernhardt, launching the “Style Mucha”—sinuous lines, floral motifs, and idealized women. But Mucha saw his talent as a divine gift, carrying a responsibility to serve a higher purpose. He declared, “I wish to be an artist who paints for the people, rather than one who pursues art merely for art’s sake.” With this conviction, Mucha created posters not just for products but as art for all, choosing the format to democratize beauty. Works like The Seasons (1896) or The Arts (1898), with no commercial tie, were affordable and visible on Paris streets, meant to uplift the masses. Yet, his vision faced irony. The models for his elegant figures were often poor women, whose reality was far removed from the flowing bouquets, lace, and ornate garments of his art. His idealized style became a fashion for wealthy salons, an escapism that defined Art Nouveau’s allure. Mucha lamented this disconnect: “I saw my works decorating the salons of high society… My time, my most precious time, consumed on these, while my homeland was like a stagnant pool drying up. In my soul, I knew I was sinfully squandering what belonged to my people.”

This frustration drove him to create The Slav Epic (1912–1926), a series of 20 monumental canvases celebrating Slavic history and identity. Donated to Prague in 1928, it responded to the formation of Czechoslovakia, reflecting Mucha’s Czech pride and vision of Slavic unity. The Beijing exhibition’s final section featured a digital, animated version of the Epic on a large screen, a choice I found misguided. In The Last Days of Jan Amos Komenský in Naarden, the original’s somber stillness conveys profound hope, but animating the grass or figures dilutes its emotional weight. Perhaps I am old-fashioned, but I believe each art form has its own language, and I am never a fan of the popular trend of “immersion” experience where famous paintings are translated into 3D projection. On the other hand, I can sympathize with the show organizers’ intention in doing so – likely an attempt to draw a larger, younger crowd with modern technology. Given his own efforts to democratize art through accessible posters, one could argue that Mucha might very well embrace all the novel methods to spread beauty!

Mucha’s Legacy: Beauty, Unity, and Revival

Mucha believed truth, love, and beauty formed the foundation of the human spirit. Art Nouveau, with its organic forms and curves, rose against the academic rigidity and the drabness of industrialization. Mucha’s flowing lines and harmonious designs offered an antidote, a vision of creation rathe than destruction. Yet, by the 1930s, as modernism embraced abstraction, his style fell out of favor, seen as outdated. After his death in 1939, his work was neglected, with The Slav Epic stored away until the 1960s.

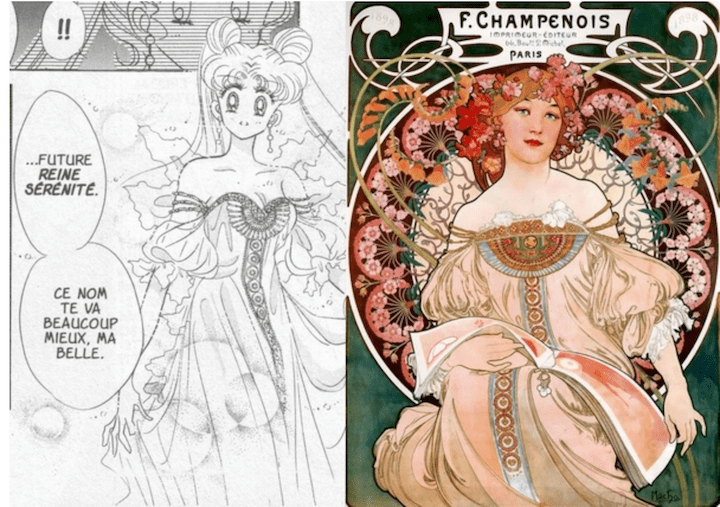

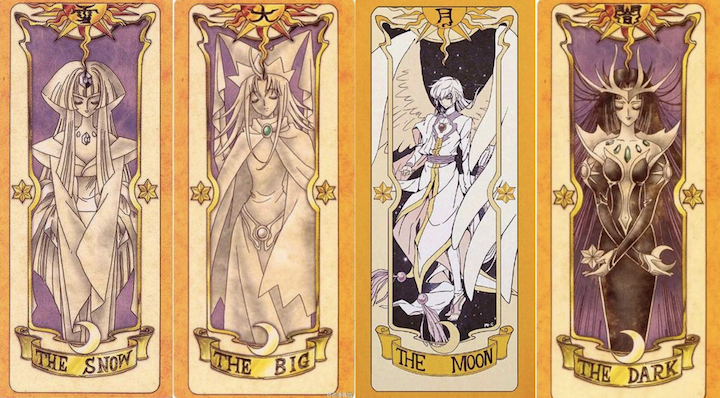

The 1960s counterculture revived Mucha’s aesthetic, his sinuous lines inspiring psychedelic rock posters and album covers. His influence extended to Japanese manga, particularly among the “Year 24 Group” of female artists in the 1970s, who pioneered shōjo manga. Works like Naoko Takeuchi’s Sailor Moon and CLAMP’s Cardcaptor Sakura echo Mucha’s floral backgrounds, geometric halos, and vine-wrapped compositions. Mucha’s influence on popular art laid the groundwork for his global resurgence, evident in recent exhibitions worldwide. This is also not the first time Mucha has been exhibited in Beijing. In fact, Mucha is so loved by the Chinese that there’s a museum dedicated to him in central China. I believe Mucha’s resurgence reflects more than stylistic appeal. Much of postmodern aesthetics prioritize incomprehensibility or deconstruction, while rejecting traditional beauty. Mucha’s art, rooted in continuous creation and human connection, offers a counterpoint. He wrote, “We must hold on to the hope that humanity can unite as one, and the more we understand each other, the closer this hope will become a reality.” His revival signals a yearning for love, beauty, and unity in a fragmented world.