[Note: The title is a quote from Spanish sculptor Francisco Baron’s preface to Car Li’s 1992 solo show in Spain.]

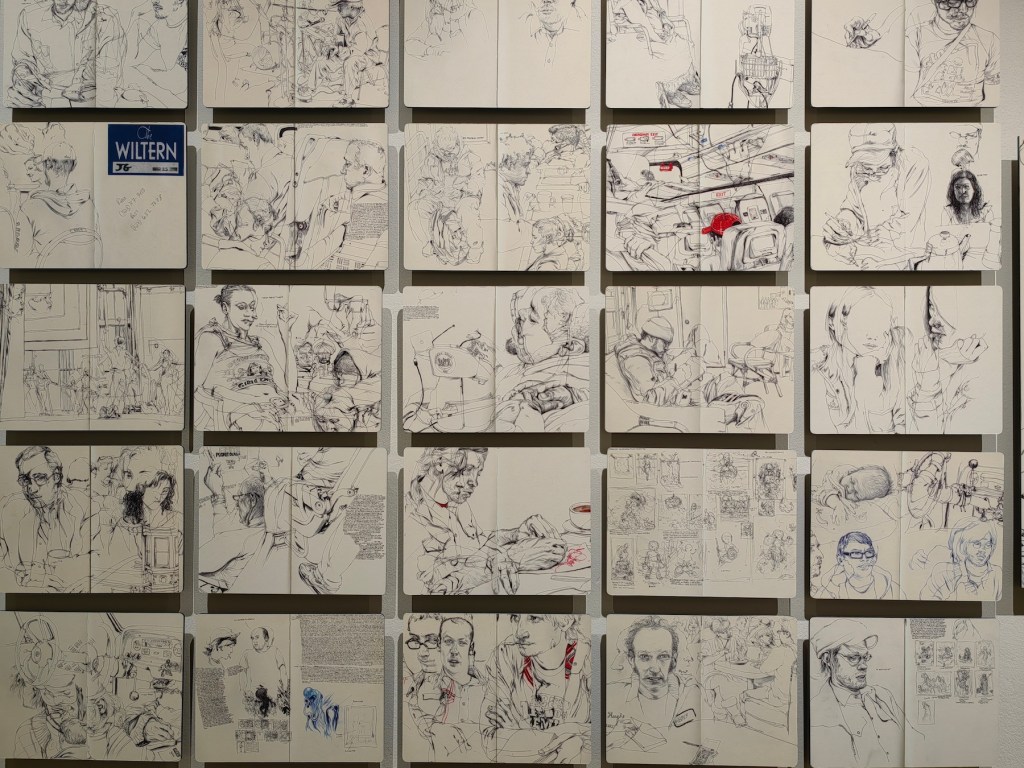

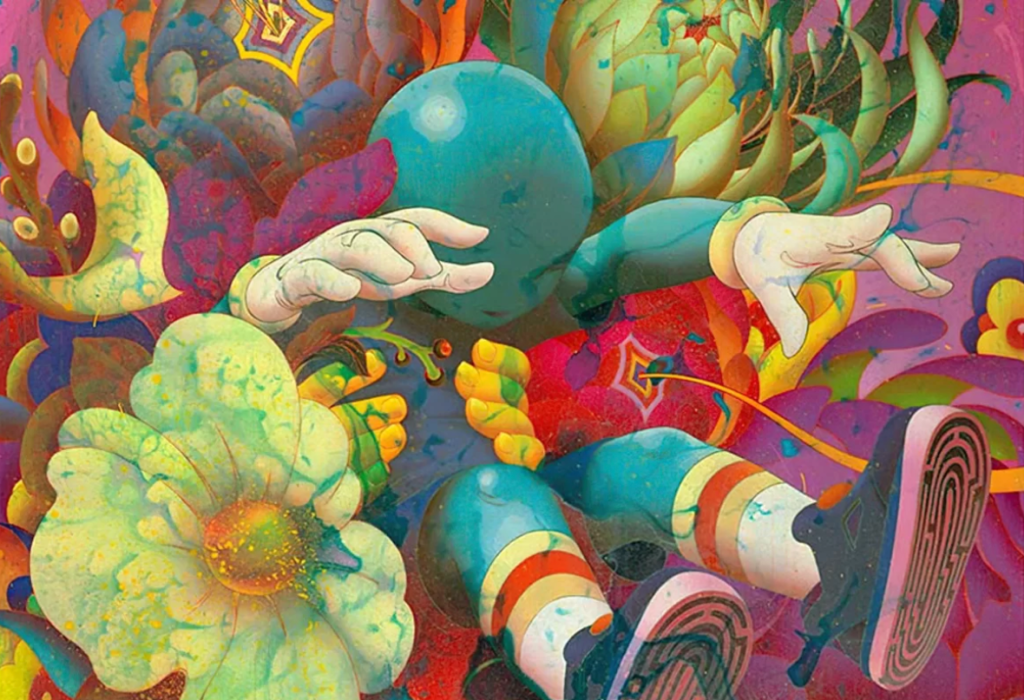

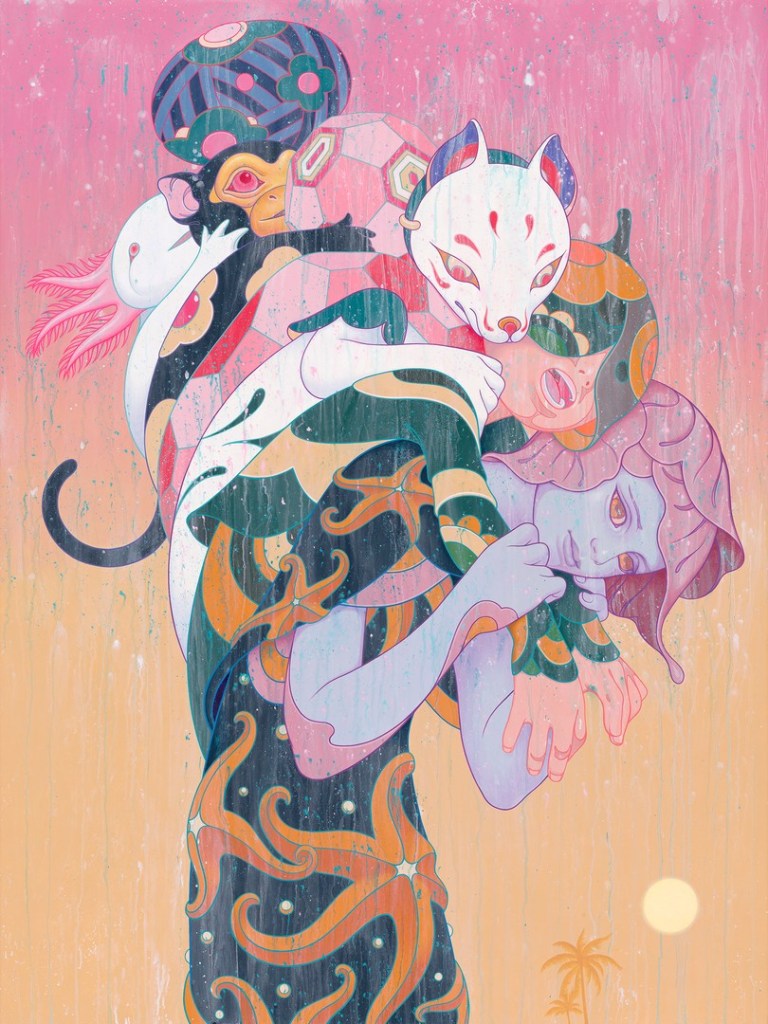

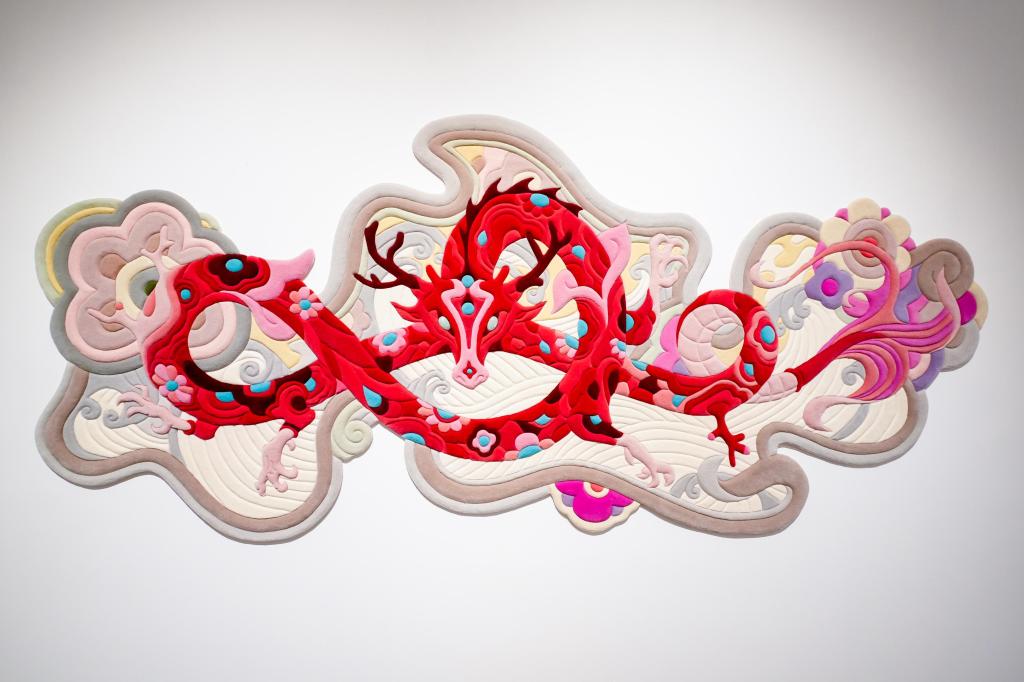

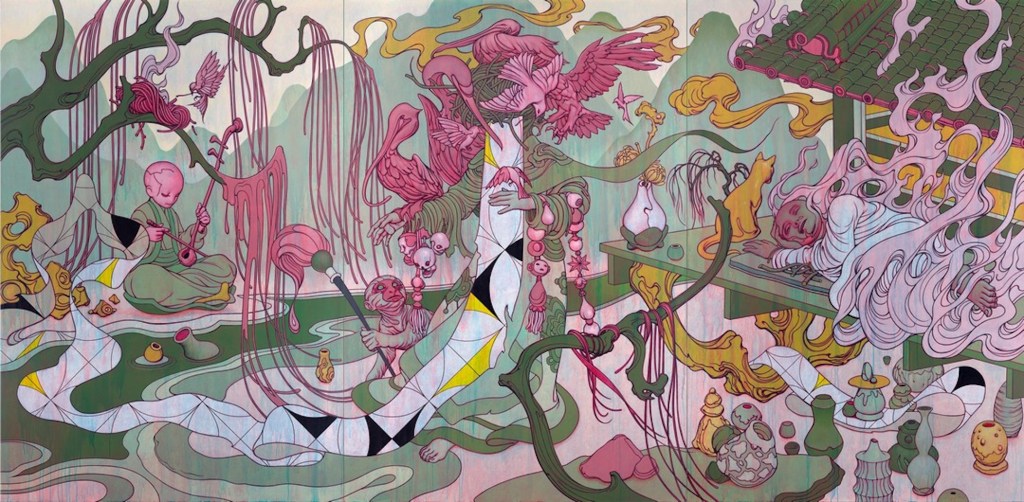

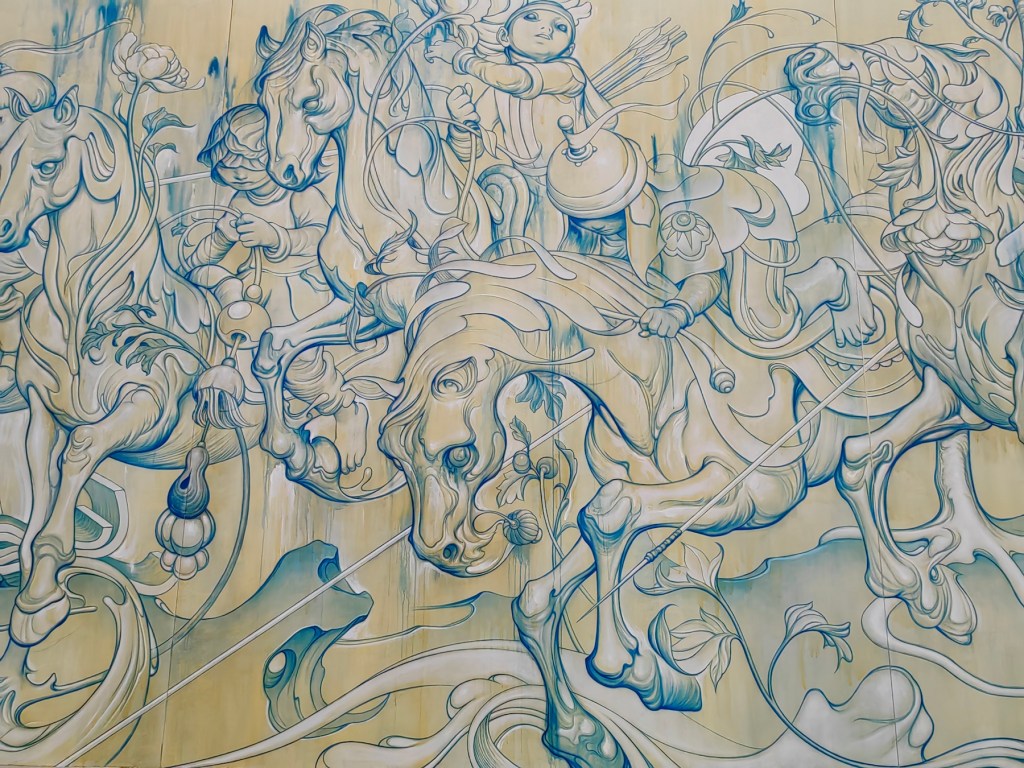

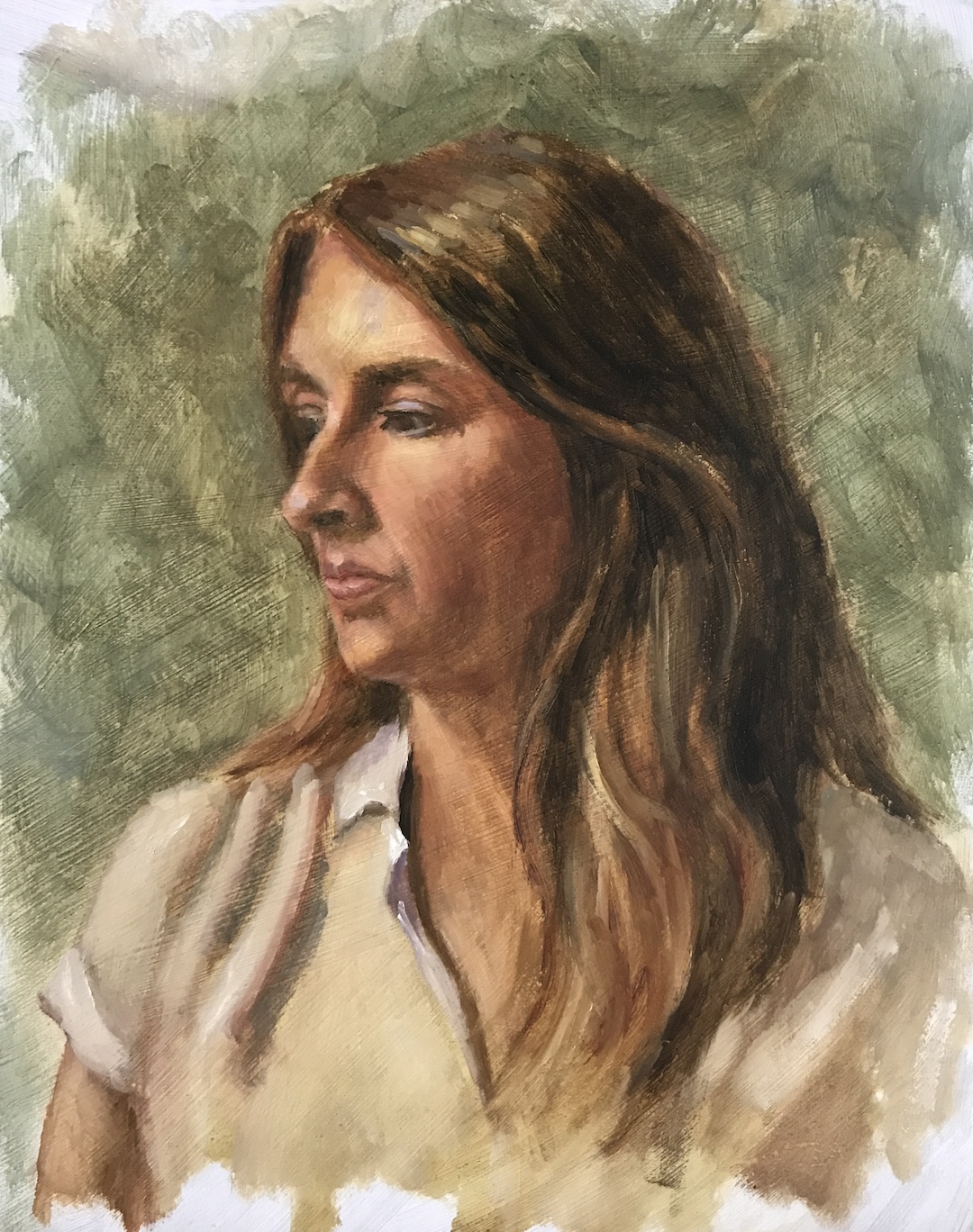

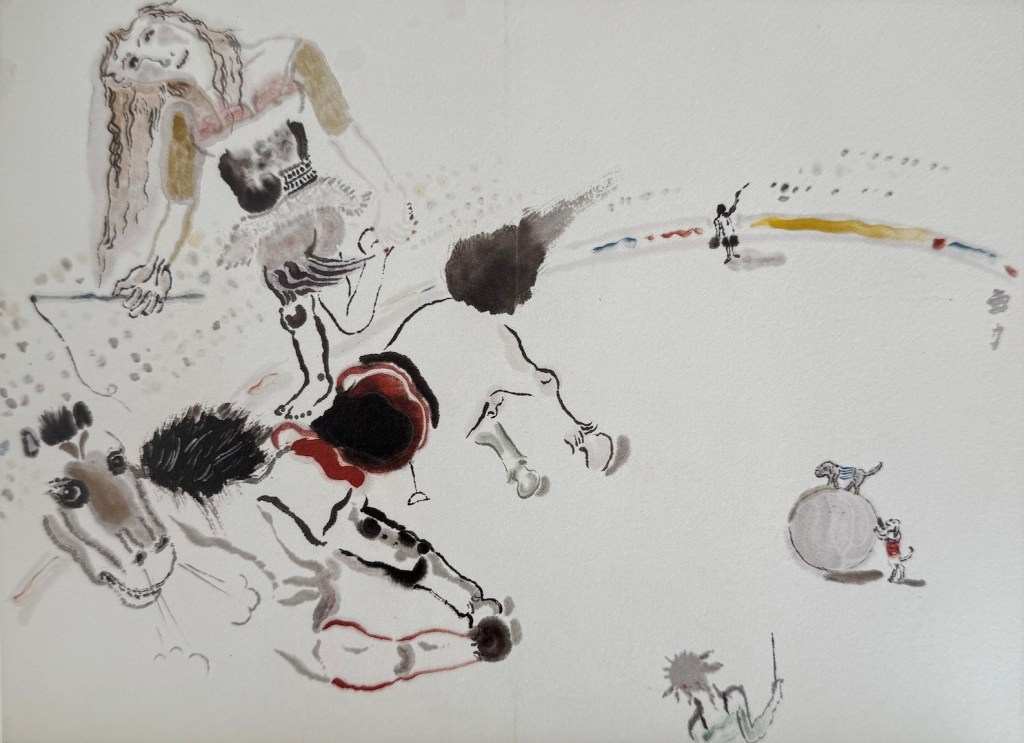

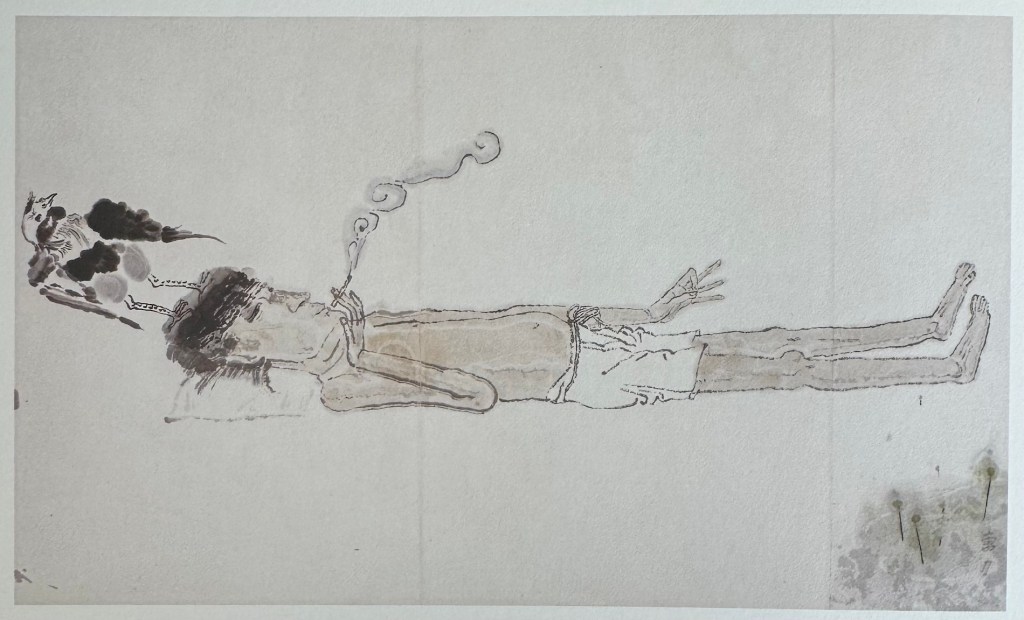

During my recent trip to China, I visited many exhibitions, and the works of one artist appeared in multiple shows, leaving a strong impression on me. He is Cao Li 曹力 (1954-), a professor of the Mural Department at the Central Academy of Fine Arts 中央美术学院. Cao Li has received traditional art training but does not carry the baggage of the academic style; in his work, he is unrestricted, and his imagination and artistic inspiration traverse ancient and modern, East and West. His themes range from reality to dreams, and his media include line drawing, watercolor, oil painting, wood carving, stone relief, etc.. His ability to move freely across different media reminds me of James Jean, though in terms of artistic expression, Cao Li is more mature and unrestrained. His works exhibit the absurdity of Dali, the seclusion of Klee, the alienating humor of Klimt, the multidimensional thinking of Picasso, the simplicity and innocence of Matisse, and the romantic imagination of Chagall. They also draw inspiration from traditional Chinese paintings, especially the murals of Dunhuang 敦煌, Yongle 永乐 Palace, and certain cave sculptures.

In the artist’s own words, “Art knows no boundaries; it is the product of the soul, an expression of true feelings, the natural flow of life, a free flight. Nature itself is not art; only what flows through the filter of an artist’s soul can be called ‘art.’ It’s like the process of making wine: grains and grapes themselves do not intoxicate, but after brewing, impurities are removed, leaving the essence that can captivate and enchant people.”

Cao Li enjoys music, a recurring theme in his paintings. His lines, compositions, and colors move like melodies, possessing a lively rhythm. Influenced by his line drawings, his oil paintings almost always start with a planar structure of lines as the initial outline and main framework. He then enriches, thickens, and adds depth to the work through the organic organization of colors. He says, “I control the blocks of color, dots of color, color areas, and lines in the same way a composer arranges notes, tones, rhythms, and tempo. Once these ‘force points’ are placed in the right spots and combined in myriad ways, the disrupted calm space is reordered.”

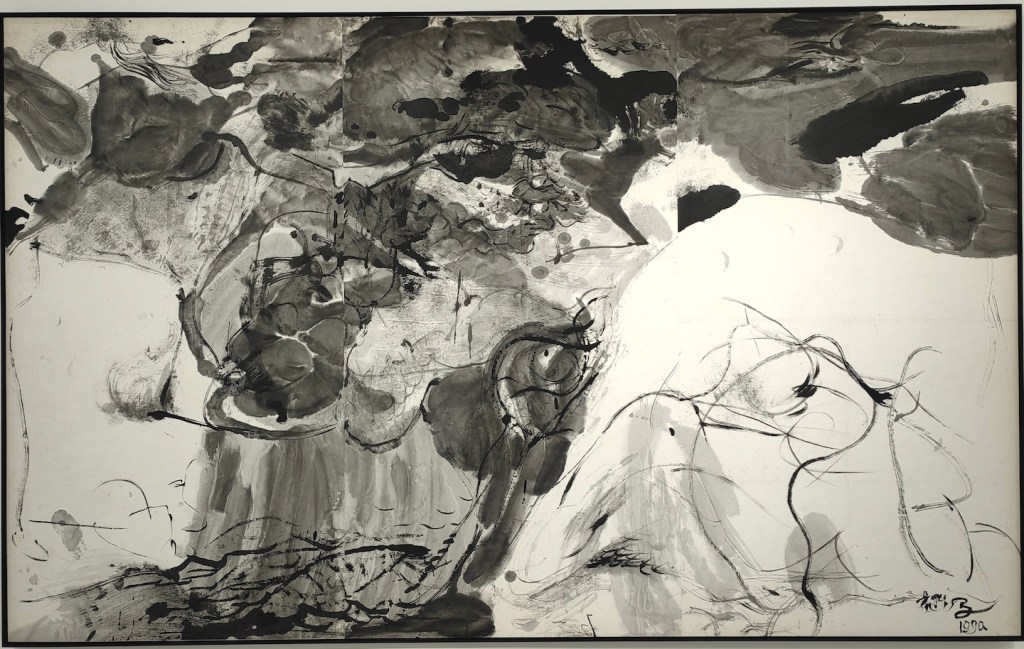

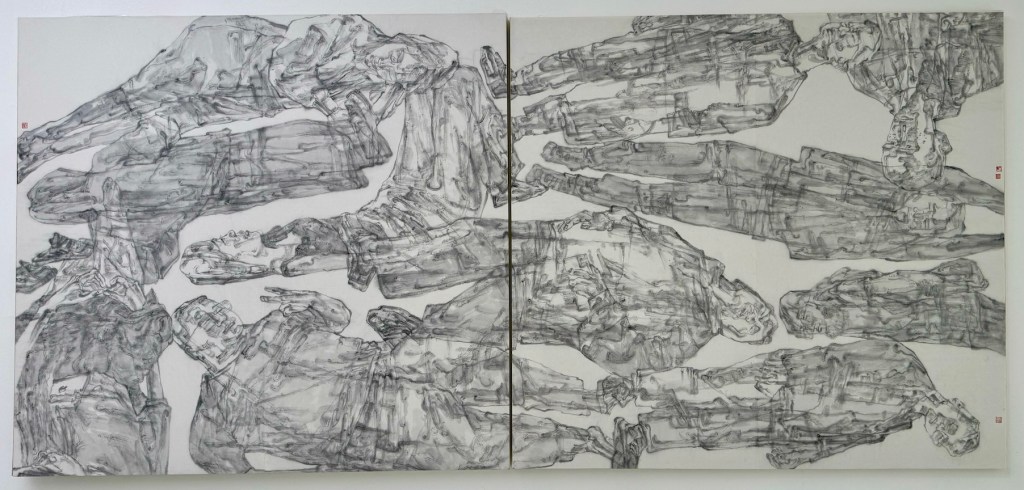

One aspect that interests me when viewing works by Chinese artists is their effort to blend traditional Chinese art with Western painting. The design of figures and the use of color in Cao Li’s works have a distinctly national character. His ink paintings even introduce modernist traditions. His teacher, the renowned artist Yuan Yunsheng 袁运生 (1937-), has taken this fusion even further by applying Abstract Expressionism to ink painting. In the 798 Art District in Beijing, I was fortunate enough to see an exhibition of his works.

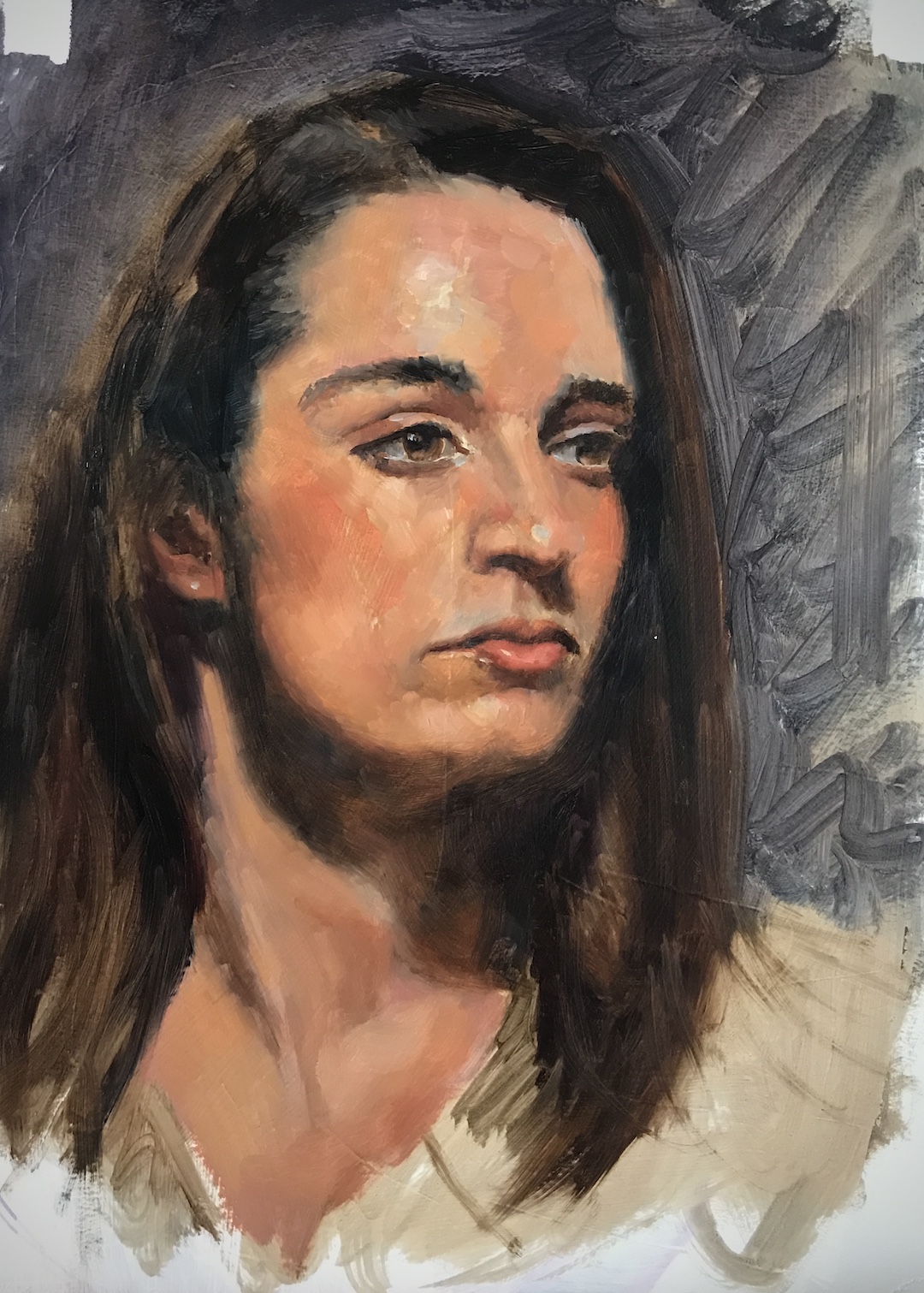

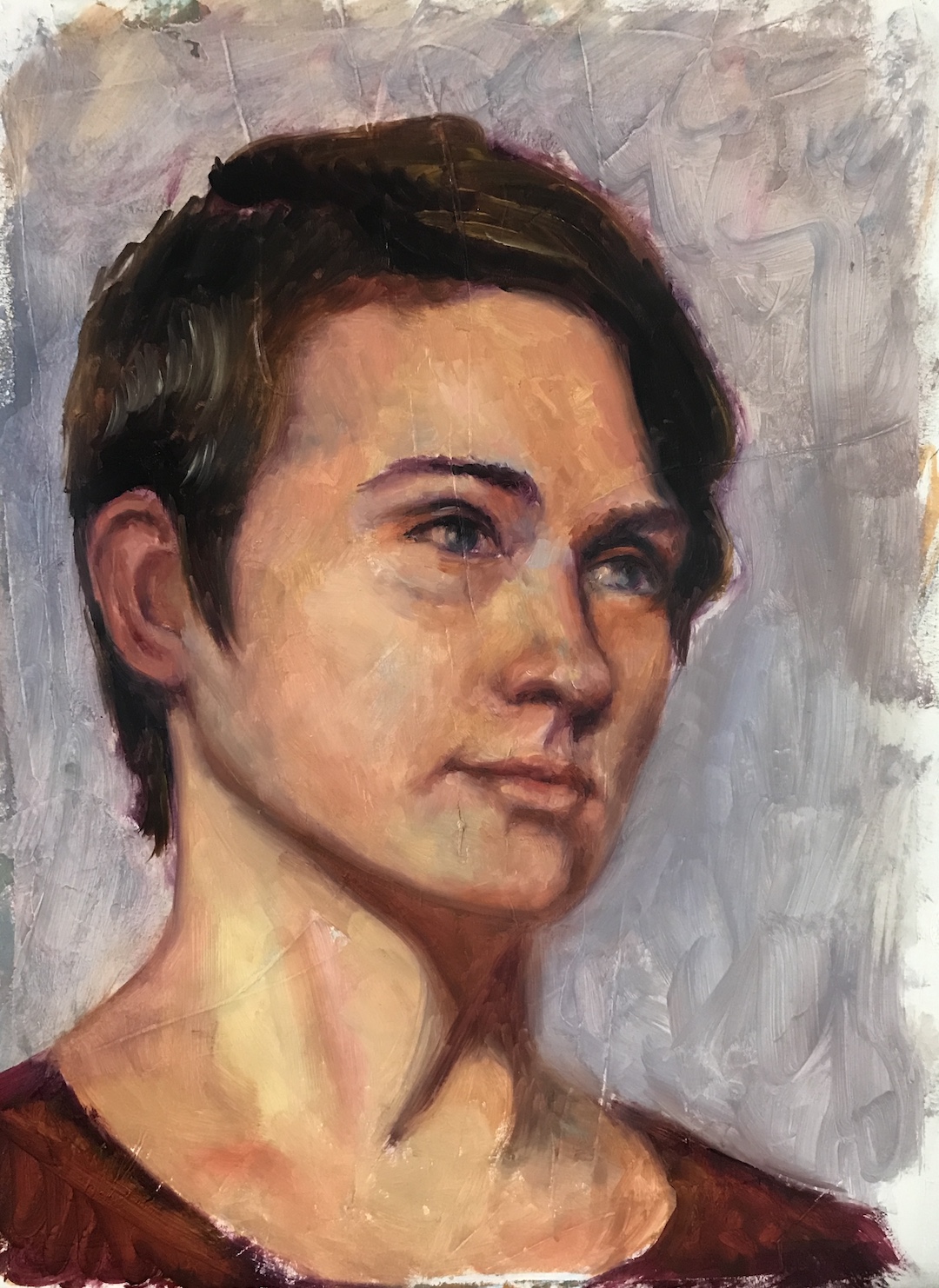

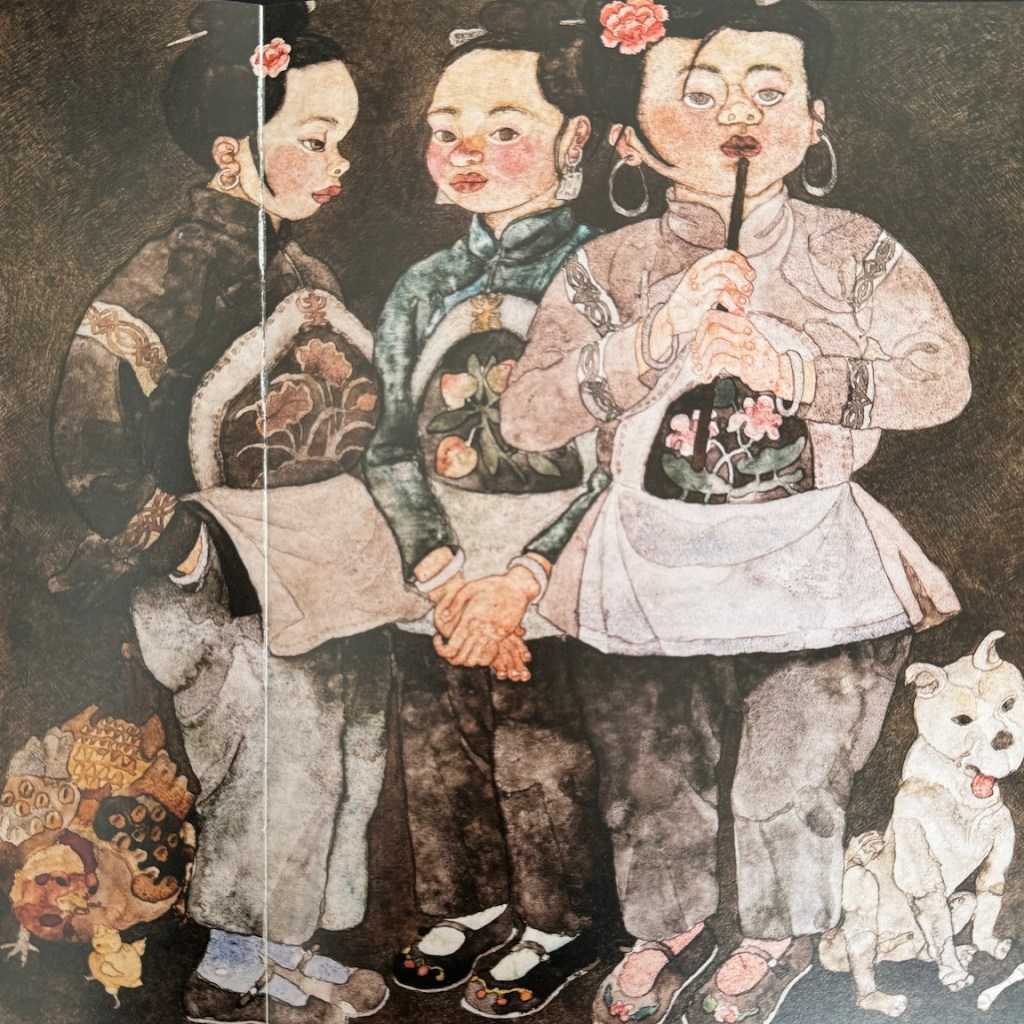

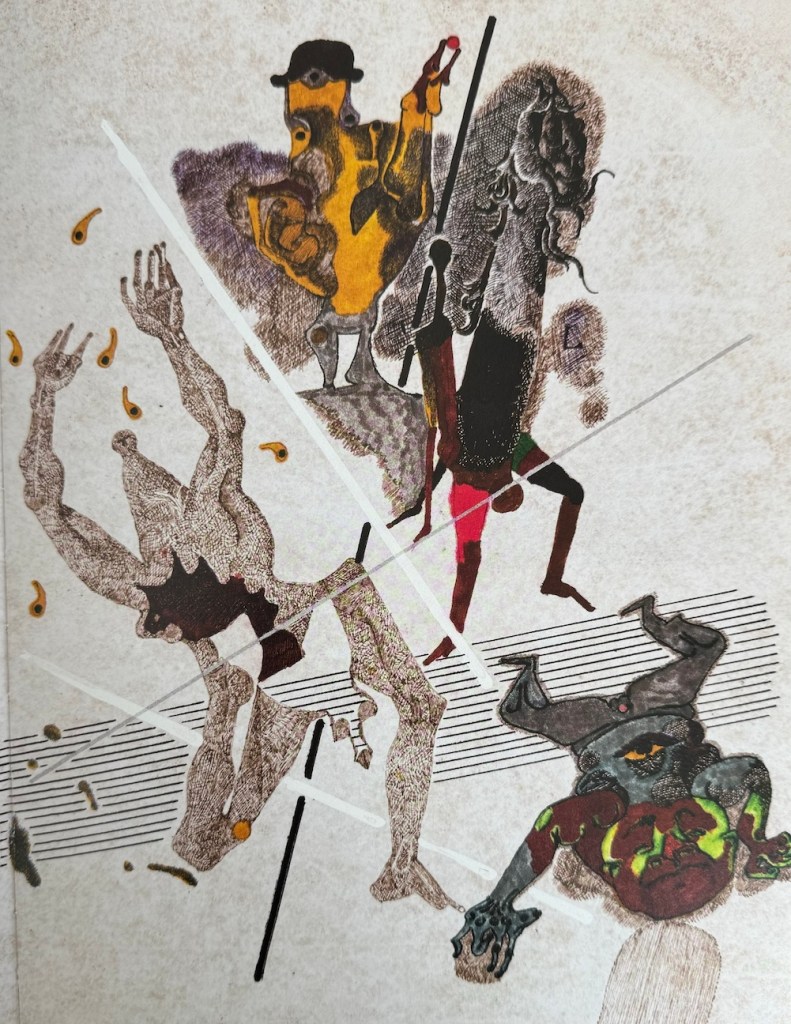

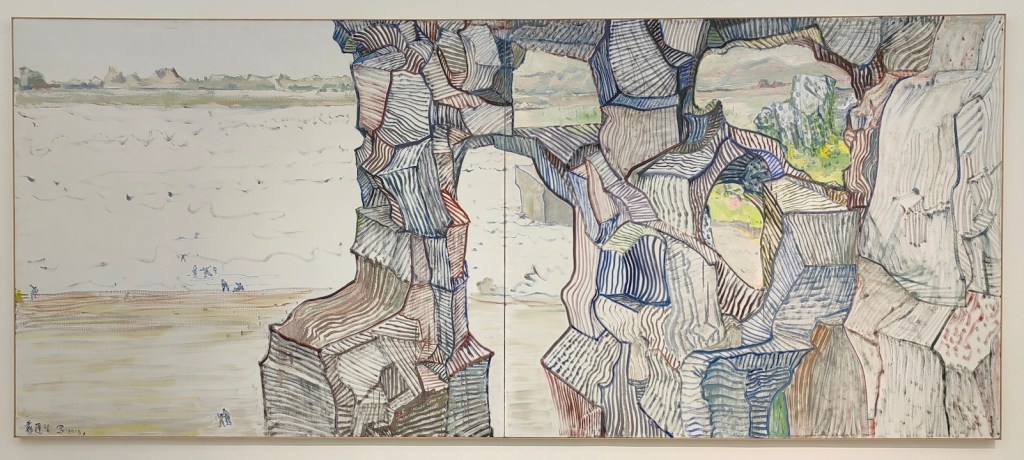

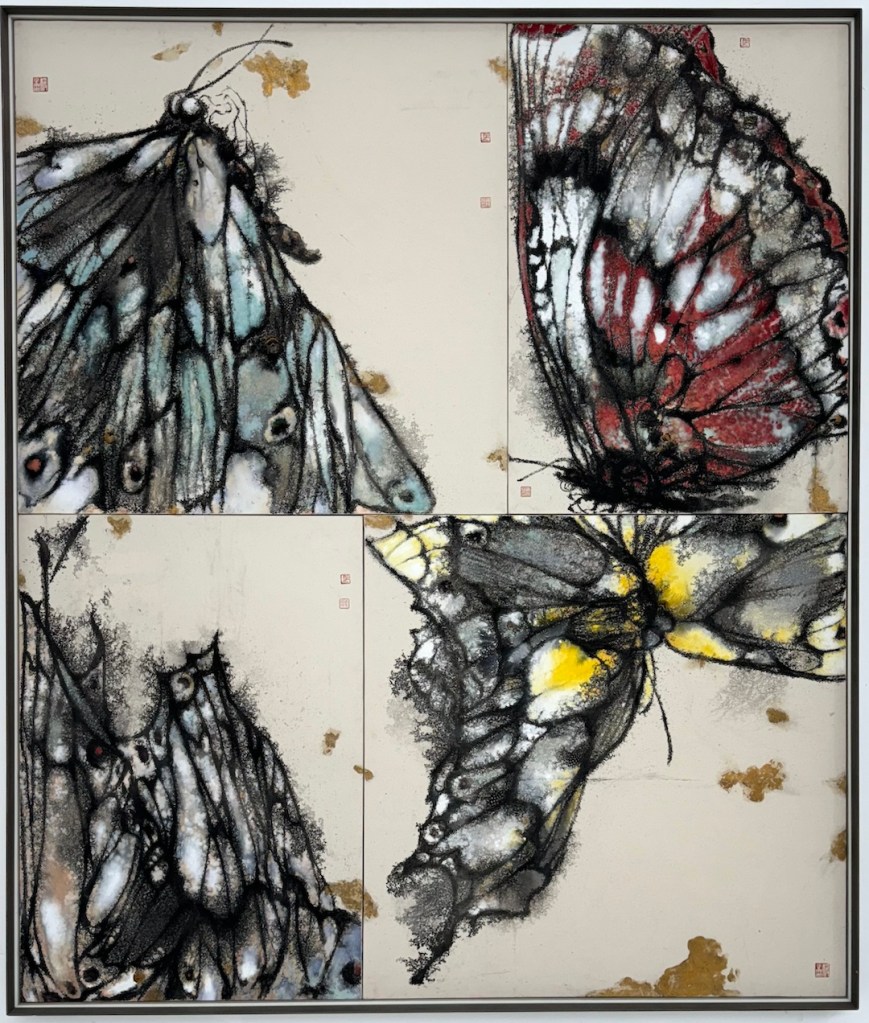

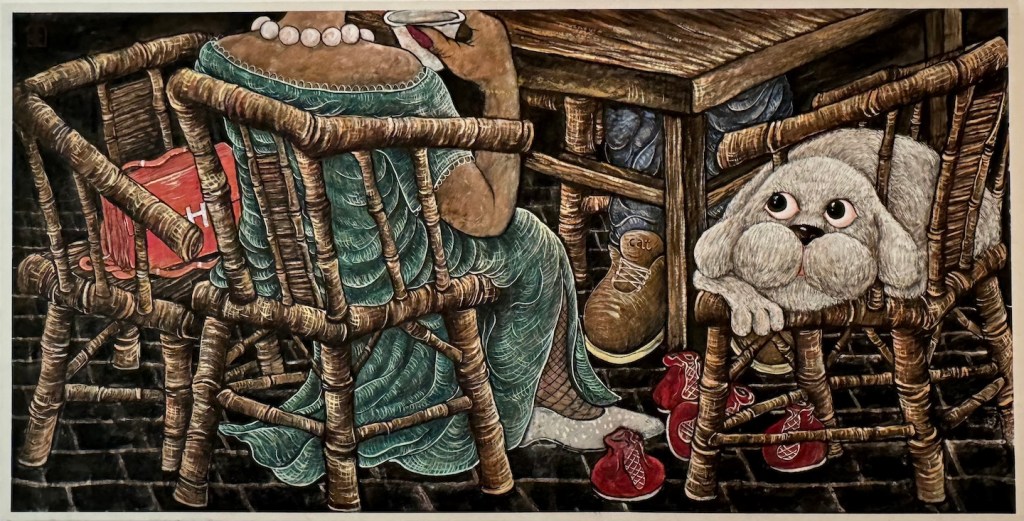

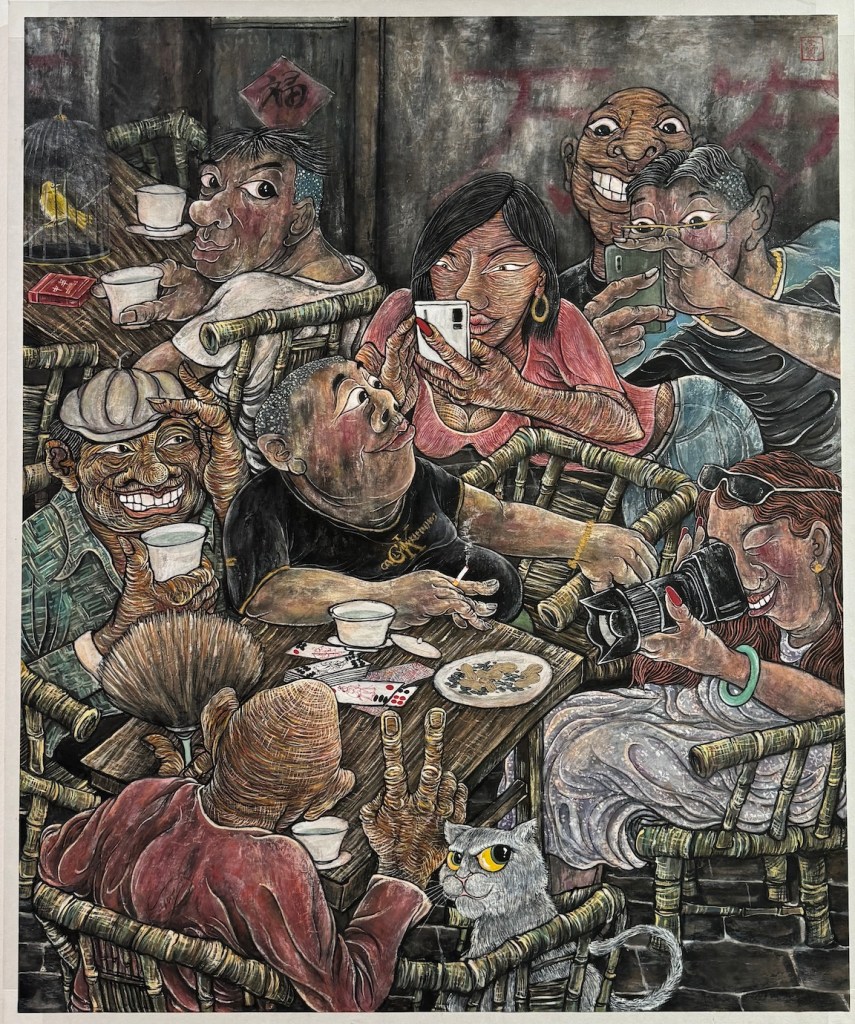

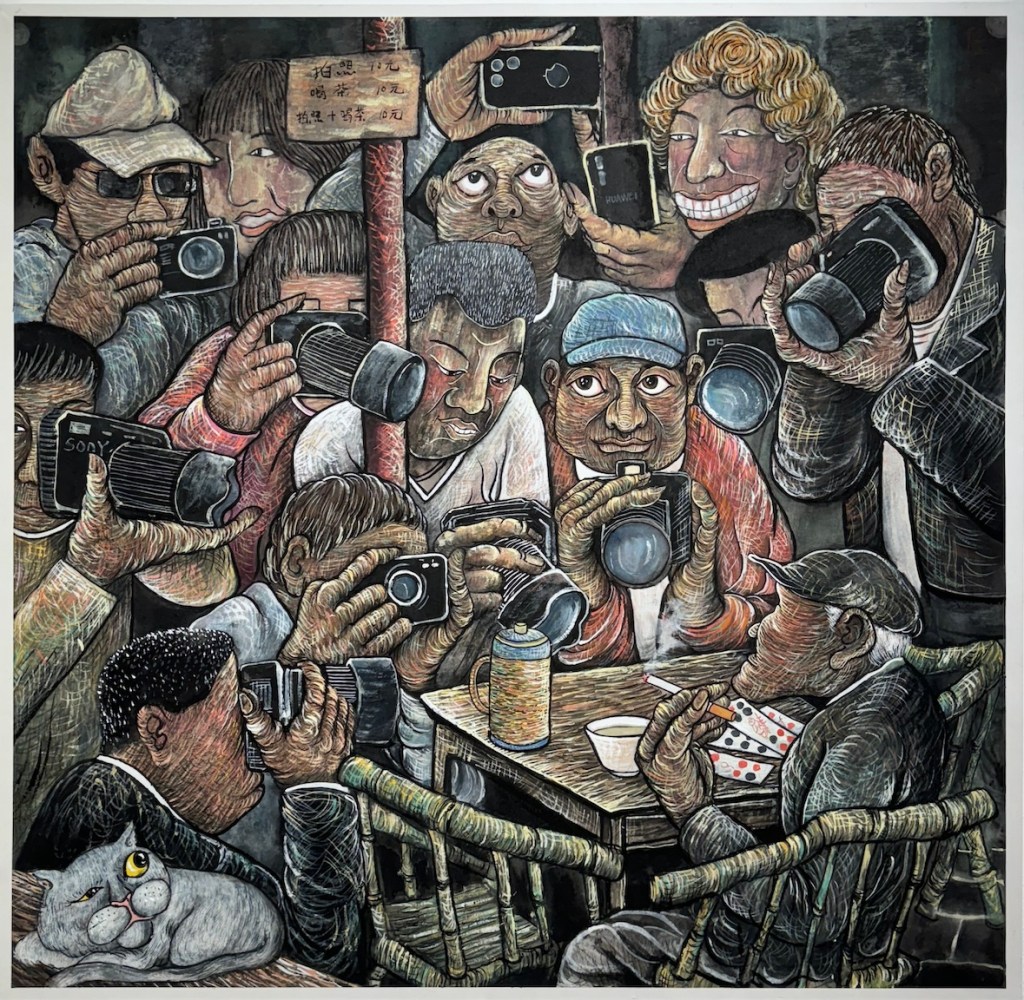

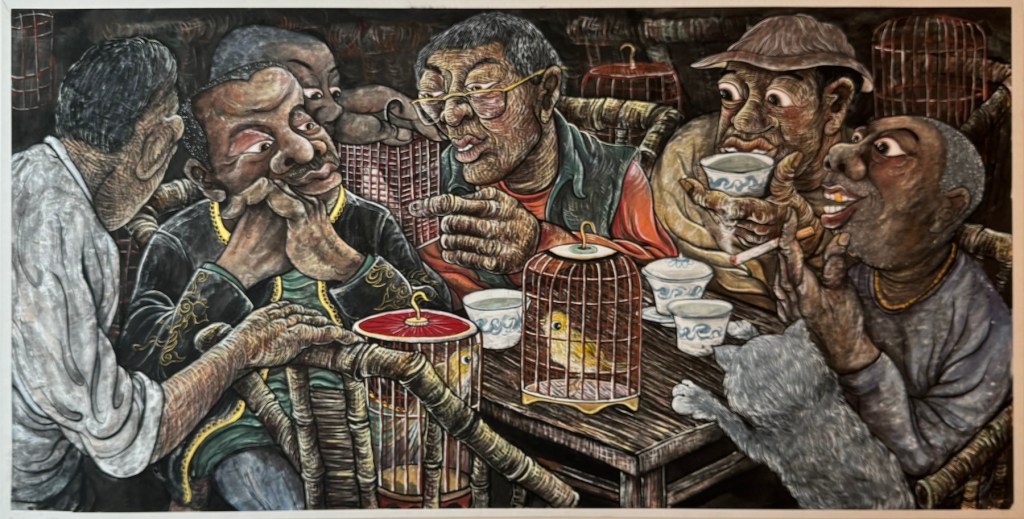

While visiting the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute 四川美术学院, I had the chance to view the “Chinese Painting MFA Invitational Exhibition 2000-2020.” These young artists originally studied Chinese painting, but now their works clearly show influences from oil painting, printmaking, and other art forms. Their use of media has also moved far beyond traditional paper and ink. They draw inspiration from the collision of diverse cultures, creating works that are more personal and profound. Unfortunately most of the artworks on display have glass cover, and makes it very difficult to photograph. I only captured a tiny portion of the treasures on display.

Here are some paintings from one of my favorite artists from the show:

Amid all the talking about the “lying flat” culture in China, it is quite exciting to see the art scene there is lively and flourishing.

P.S. Unlike in America, most of the Chinese artists don’t maintain personal websites. Artron 雅昌 is platform where many artists post their works, but the level of accuracy and maintenance vary. You can find more works from Cao Li here: 作品