January brought me home after a long stretch away, and for the first time in months I finally had time to just zone out, daydream, and do some belated New Year planning.

As someone who’s deeply introverted and home-loving, I actually spent quite some part of last year outside my comfort zone. I visited many exhibitions, immersed myself in incredible paintings by other artists, and played extensively with AI image generation. Those experiences were thrilling in their own ways. I’m still in awe of what AI can conjure in seconds, and I still find it genuinely useful as a brainstorming and reference tool. Yet all of it, the shows, the scrolling, the endless prompting, only made my hands itch to pick up a brush. Nothing digital or vicarious can match the slow, stubborn satisfaction of standing at the easel for three or four hours, building something stroke by stroke, decision by decision, until it finally exists.

In parallel, I’ve been revisiting watercolor through basic exercises focused on values, color relationships, temperature, and edge quality. These aren’t flashy pieces; they’re deliberate drills. But every time I return to them, I’m reminded how deceptively simple the core theories of painting really are and how easy it is to overlook one of them the moment I get excited about a subject. When a painting fails (or just falls flat), it’s almost always because I ignored or half-applied one of those fundamentals.

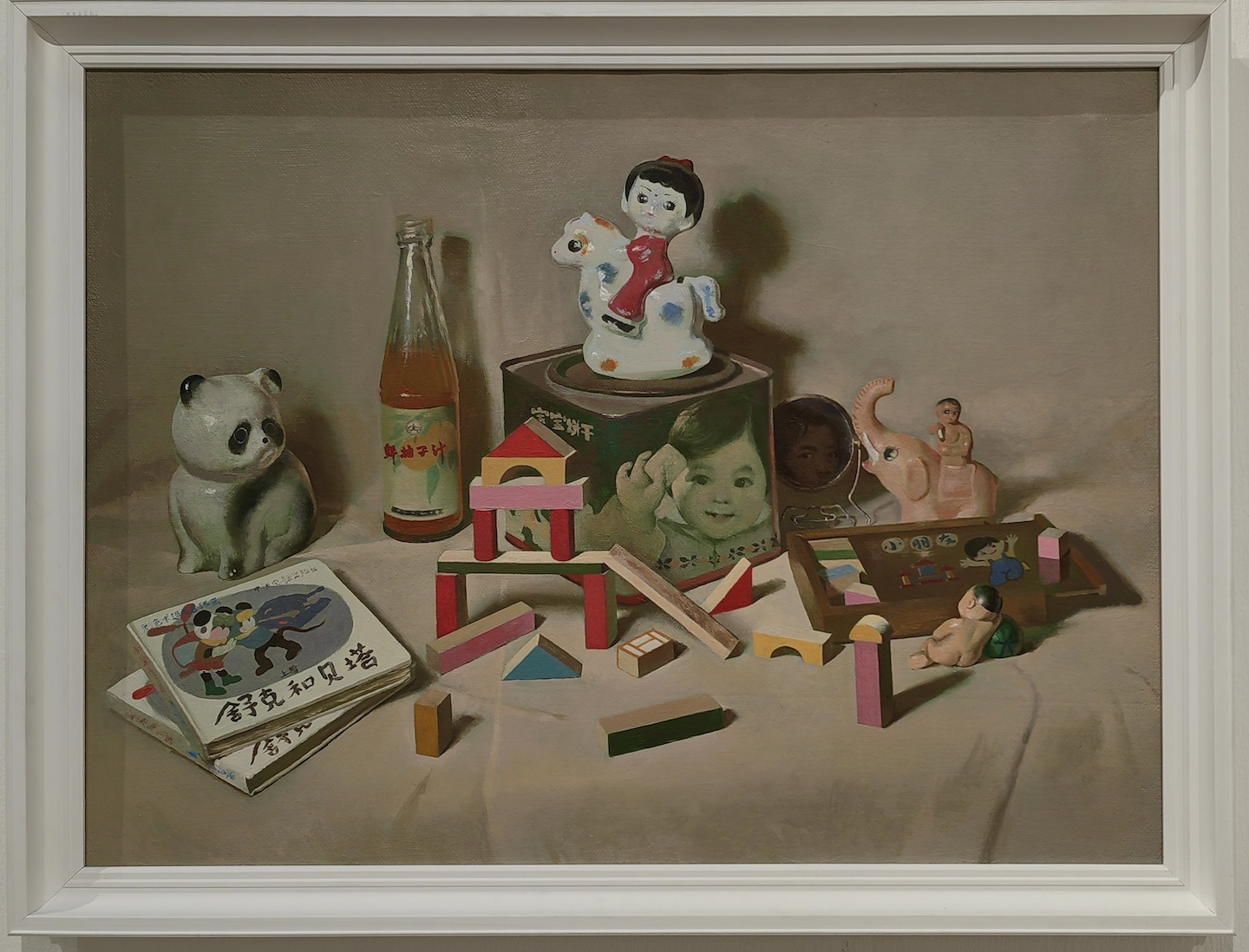

While reorganizing my studio recently, I pulled out a few unposted oil still life paintings from last year. Seeing them with fresher eyes—after months of looking at masterworks and grinding through exercises, I can now spot exactly where I leaned too heavily on “copying what I saw” instead of using what I know.

My shapes and overall compositions still hold up; I’m happy with those choices. But the values? In several passages I could have orchestrated them more deliberately to create stronger focus, depth, and mood. For instance, “Group Portrait 1”, for the small white cup and the dish in the center, the reflective surface and the blue strips makes the lighting not as informative as on others. I wrestled with those forms for hours. Now I realize I could have analyzed and designed the value patterns based on my knowledge (where the lightest light, darkest dark and mid-tones should be given the light source and the object’s shape), and considered their roles in the whole picture. With more intentional grouping and subordination, those objects could have popped or tucked in with far less effort.

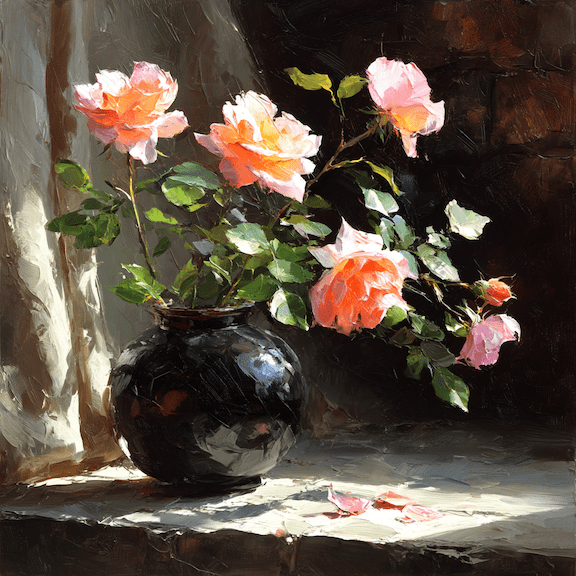

The roses suffered from a similar issue. I got lost in distinguishing individual petals too soon, instead of first establishing the big value structure across the entire bouquet, then each rose. Had I done that, the flowers would feel more alive and integrated.

Color-wise, I still like the overall harmony in these pieces. The palettes feel cohesive and quiet, which suits my taste. But there’s room to push sophistication further. In the roses, I could have borrowed subtle echoes of the background tones into the petals themselves to make the roses more atmospheric. In the “Group Portrait 2”, I could have let the objects’ colors bounce into the paper underneath, unifying the scene better.

These aren’t harsh self-criticisms: they’re just clearer observations now that I’ve had distance and review. The artists whose work I admire most probably didn’t arrive at their mastery through secret techniques; they simply became relentlessly consistent at remembering and applying the fundamentals while they painted.

So for 2026, I’m keeping the plan very simple (and hopefully realistic): I want to strategize how to apply what I know and constantly remind myself of the fundamentals during the process, making every session an effective practice. Who knows? By the end of the year, these conscious efforts might turn into subconscious habits, and I might finally make the progress I’m looking for.